Ι. Preamble

“Prisoner’s dilemma”: A standard example of a game analysed in game theory, the study of mathematical models of strategic interaction among rational decision-makers. This dilemma, as well as this theory, probably does not regard everyone.

Other dilemmas seem to be more familiar:

“Oh but I think I am in trouble, don’t know if I want to choose Kiki or Koko. I do love Kiki but I also like Koko”. Us elders most likely have shared the dilemma of singers Spiros Koronis and Filandros Markou.

The Private Company (PC) was introduced in the Greek legal system in April 2012, while Société Anonyme and Limited Liability Companies still existed.

The boundaries between a PC and an SA were (and still are) pretty clear.

This is not the case with the boundaries between a PC and an Limited Liability Company.

Or is it?

And in reality: Which was/is the best choice?

The (pretty) “new” PC or the “already tested” Limited Liability Company?

ΙΙ. The legal status of a PC and an Limited Liability Company

A PC and an Limited Liability Company is somewhere between a public company limited by shares (e.g. an SA) and partnerships (e.g. a General Partnership and Limited Partnership).

Both PC and Limited Liability Company are considered to be closer to public companies limited by shares. But they still have many similarities with partnerships. Those elements that make them resemble partnerships are either imposed by law or can be introduced with the company’s articles of association.

What is certain is that those two companies have some distinct differences. A comparative overview will securely lead us to which one of the two is superior.

ΙΙΙ. Establishment:

1. Regarding PC

A PC is established and amended with a private document. The speed and low cost of establishing and amending it is one of the main reasons why it is, at least at a first glance, so appealing.

But the “private document rule” does have some exceptions.

A notarized document is mandatory for a PC in some specific cases. In case, for example, that such is required by a specific law or when specific assets are contributed to the company, whose transfer requires a notarized document (e.g. immovable property or rights in rem in immovable property). Additionally, a notarized document can be chosen by the company’s founders or founder (when talking about a single member PC) (article 49 act 4072.2012).

2. Regarding Limited Liability Company

Until recently, the establishment and all amendments of a PPC could only take place with a notarized document (article 6§1 act 3190/1955). This rigidness of PPC was, on its own, a good enough reason to avoid this company type.

Relatively recently (article 2 §2 ν. 4541/2018) par. 1 of article 6, act 3190/1955 was amended. This amendment introduced allowed the establishment of PPC either with a private document or a notarized one.

A notarized document is required only in specific cases. When, for example, such a document is required by a specific law or when specific assets are contributed to the company, whose transfer requires a notarized document (e.g. immovable property or rights in rem in immovable property). Additionally, a notarized document can be chosen by the company’s founders or founder (when talking about a single member Limited Liability Company).

A private document (and not a notarized one) is deemed enough when the official model articles of association are adopted. In this case, though, the establishment of the LLC can be realised by any “one stop shop”, as such is appointed by law (act 4441/2016). Meaning: (a) by the Business Registry departments of the Chambers of Commerce, (b) by “one stop shop” notaries, (c) online, in e- “one stop shop” (which, for the time being, only works for PC companies) -and not exclusively before a notary (1 Common Ministerial Decision No 63577/2018).

What is, though, the main issue? In cases where the official model articles of association must be used, they must be used exactly as they are given, with no alterations. If the official model articles are altered, and the founders choose to establish the company with a private document, this will constitute a ground for the LLC’s invalidity.

Therefore, in cases where an LLC’s founders want to deviate from the official model articles of association, a notarized document is the only option. The relevant burden on the founders (timewise and moneywise) can simply not be avoided.

3. Conclusion

Based on what we established above, we come to the conclusion that, as far as the establishment of the two companies is concerned, PC is the clear winner. Therefore:

Private Company-Limited Liability Company: 1-0

ΙV. Capital:

1. Regarding PC

PC’s capital is determined by its partners without limit, it can even be a zero capital. Its partners can partake in the company with capital, non-capital contributions or guarantee duties (article 43 §3 act 4072/2012).

2. Regarding Limited Liability Company

LLC’s capital is determined by its partners without a limit (lowest or highest). It is formed either with cash or with contributions in kind (article 4 § 1 act 3190/1955).

Previous version of the article required a minimum capital deposited in the LLC. It started (:1995) with a requirement of a minimum capital deposited of 200.000 drachmas. Consecutive increases had it reach 18.000€ (:2002). Consecutive decreases followed. Today, the requirement for a minimum capital deposited has been abolished (article 3 § 9 act 4156/2013). But LLC’s capital cannot be zero.

3. Conclusion

According to the above, we come to the conclusion that, as far as capital is concerned, at least in a theoretical level PC seems to prevail, since its capital can be zero. On the other hand, an LLC can be established with a capital of 1€. So we should probably call it a tie – no company type prevails, no point is appointed. The score remains:

Private Company-Limited Liability Company: 1-0

V. Partner’s contributions:

1. Regarding PC

We have already mentioned (above under IV.1) that several kind of capital contributions can be made in a PC. A partner can participate in a PC’s capital by contributing money (:capital contributions). Additionally, they can participate by making non-capital contributions or by having guarantee duties (article 76 § 2 α΄ act 4072/2012). A necessary precondition in order for someone to participate in a PC is to acquire one or more shares (article 75 § 1 α΄ act 4072/2012). Each share represents only one type of contribution (article 76 § 2 b΄ act 4072/2012).

As a result: it is possible that a PC has received no capital, but only guarantees and non-capital contributions. The latter (guarantees and non-capital contributions despite that the have a value) they can render PC’s capital a zero-capital.

But which are the non-capital contributions and what are the guarantees?

The non-capital contributions are those contributions that cannot constitute capital contributions. Such are claims that derive from an undertaking of an obligation to execute works or to provide services. The value of these contributions undertaken when the company is established and/or afterwards, is determined in the company’s articles of association and is freely estimated by the partners (article 78 §§ 1 and 2 act 4072/2012).

The guarantee duties undertaken by a partner mean that this partner has a guarantee duty for any company debt owed to any lender. The partner’s liability entails covering the company debt (the balance of capital, interest and other charges) up to the amount determined in the company’s articles of association. In this case the partner is liable before the lenders as if they were the principal. The lenders can turn directly against the partner. There is no preliminary procedure. It is also not a requirement for the lenders to first turn against the PC to prove that the company cannot pay them off, before they turn against the partner burdened with a guarantee duty.

The option given for a non-capital contribution and of a contribution made by undertaking a guarantee duty makes it possible for someone to become a partner in a PC, even if they do cannot or do not want to make a capital contribution.

The provision allowing for non-capital contributions or contributions made by undertaking guarantee duties makes a PC resemble a partnership. By providing these options, the partners are free to choose if they will be more like a partnership or an SA.

2. Regarding Limited Liability Company

There is no provision for non-capital contributions or contributions made by undertaking guarantee duties in an LLC. An LLC’s partners are obligated to contribute money. Alternatively: they can make contributions in kind, but they must be material.

Even in a case were one of the LLC partners undertakes the obligation to work for the company or undertakes the obligation to pay company debt, they will not be looking at receiving company shares because of those reasons.

3. Conclusion

Things are simple. A PC offers the option of making non-capital contributions or contributions by undertaking guarantee duties. LLC does not.

PC prevails. The score now clearly is:

Private Company-Limited Liability Company: 2-0

VI. Decision-making:

1. Regarding PC

Each company share carries the right for one vote (article 72 § 2 α΄ act 4072/2012). This means that PC’s partners form their decisions (in an assembly or not -under the provisions of the articles of association and of the law) with the majority of the votes/majority of the shares.

2. Regarding Limited Liability Company

LLC is more complex.

According to article 13 of act 3190/1995: “Unless otherwise provided by law, the decisions are made by the majority of the partners, provided this majority is formed by more than the half of the partners, representing more than half of LLC’s capital”. This means that, in order for a decision to be made in an LLC, two majorities are required: of capital and partners.

This legal requirement quite often creates significant problems. Even in cases where a partner has more than half (even more than 99%) of the capital, they are not entitled in making decisions. A necessary requirement for the decision to be made is for the partners who could have a minimum participation to agree with the partner holding the majority. In case that the first are outnumbering the majority partner(s), they have the opportunity to even extort, under the threat that they will oppose to a specific proposal. This fact renders LLC dysfunctional. It is quite possible that in some cases it will be impossible to reach a decision, when there are opposing partners who, even though they hold the minority share of the LLC’s capital, still outnumber the majority holder(s).

3. Conclusion

It is also clear. PC prevails as far as decision-making is concerned. The score now is:

Private Company-Limited Liability Company: 3-0

VΙI. Partner’s social security contributions:

1. Regarding PC

One more advantage of PC when compared with LLC is the lower social contributions owed by PC to the National Social Security Entity. The relevant issues are clarified in the National Social Security Entity’s circular no. 21/22.4.2019. Briefly:

The partners of multi-membered PCs do not have to have a social security. The partners have the option of being insured according the provisions of the Self-Employed Workers’ Insurance (article 116 § 9 b΄, act 4072/12). Only the partner of a single-member PC must be insured accorrding the provisions of the Self-Employed Workers’ Insurance (article 116 § 9 a΄, act 4072/12).

Nonetheless, PC’s managers must be insured. To be more precise, the following persons must be insured according to the provisions of the Self-Employed Workers’ Insurance (article 116 § 9 a΄, act 4072/12): (a) the partner of the single-member PC who is also its manager, (b) the partner of the multi-member PC who is also its manager, (c) PC’s manager who is not a partner, but has been appointed as the manager by the company’s articles of association or with a decision made by the partners.

2. Regarding Limited Liability Company

In contrast with PCs, LLC’s partners must be insured (article 39, act 4387/2016). Respectively, LLC’s partners who are also the company’s managers in exchange for a fee, are obligated to make relevant to their fee social security contributions as per article 38, act 4387/2016. Lastly, LLC’s manager, when they are not also a partner, they do owe social security contributions for the fees they receive, also according to article 38, act 4387/2016.

3. Conclusion

The financial burden imposed on LLC partners are clearly more significant than those imposed on PC partners. PC prevails here as well. The score is:

Private Company-Limited Liability Company: 4-0

VIΙΙ. Getting back in business

1. Regarding PC and Limited Liability Company

Both PC and LLC can be dissolutioned, after, among others, a decision made by the partners, because the company’s duration expired and because of bankruptcy. In both those cases, both company types can get back in business, after a unanimous decision of their partners (article 105 §7, act 4072/2012 and article 50a act 3190/1955). The difference between the two is that a PC can get back in business even after the process of distribution of its assets has started. This cannot happen in LLCs.

2. Conclusion

PC prevails here as well.

The final score is overwhelmingly in favour of PC:

Private Company-Limited Liability Company: 5-0

IX. The trust of the market in PCs and Limited Liability Companies

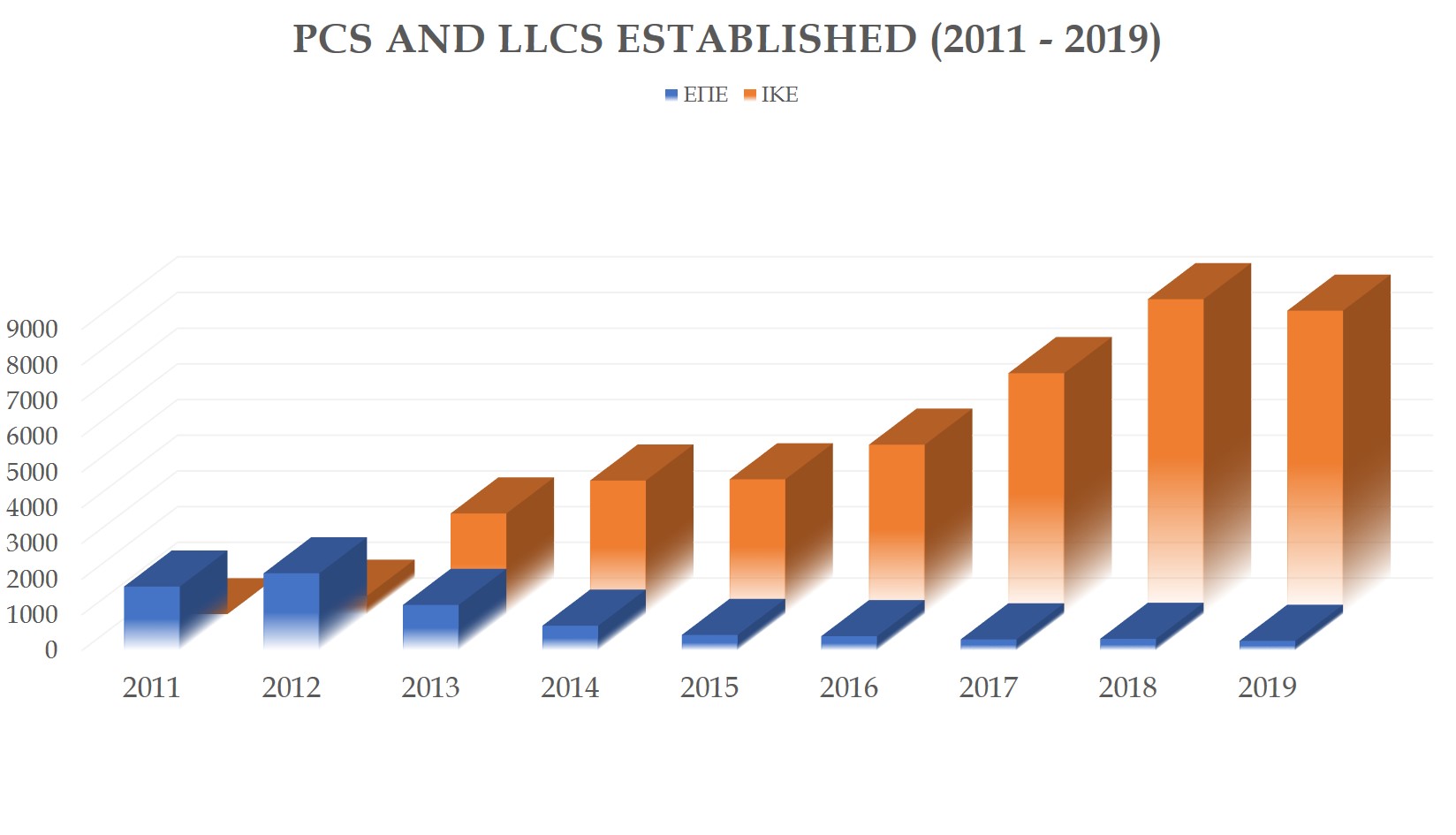

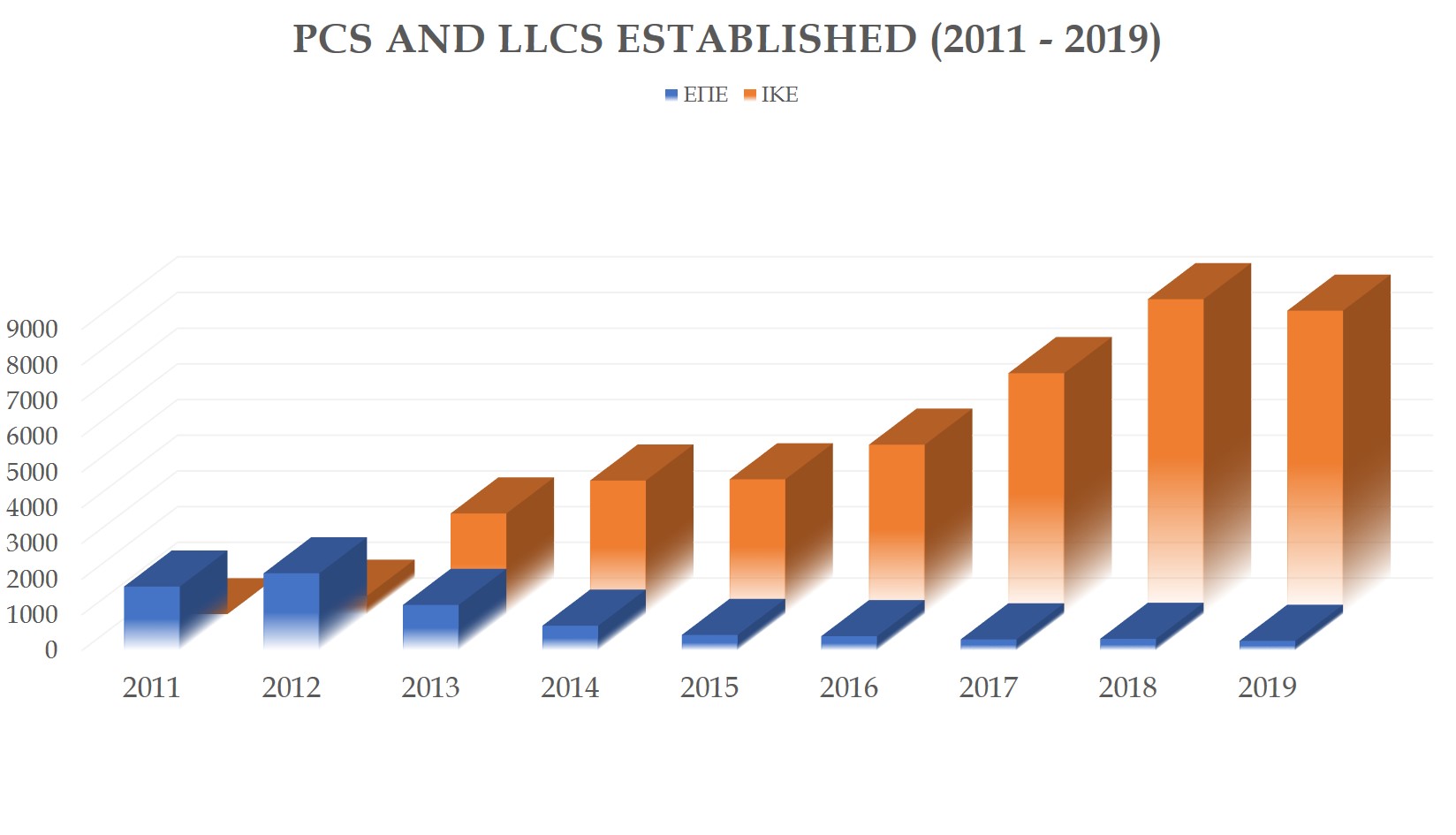

Since the act on PCs was published (Government Gazette A’ 86/11-04-2012), businessmen, accountants and lawyers showed their complete faith in PCs. (Our Law Firm established the second ever PC in Greece.) Business Registry’s data for the years 2012 (when PC was established) until mid-October 2019 confirm the trust of the parties involved. Overwhelmingly in favour of PCs. And to be more precise:

X. In conclusion

PCs and LLCs have been competing each other, since the day PCs were established.

PCs prove more cost efficient when compare to LLCs. The most important difference between the two, though, is that PCs prove to be more flexible.

PC’s partners have a lot of room for initiatives, in order to manage important company issues as they think best. The advantages of PCs compared to LLCs are more than clear.

The trust the market has shown in PCs is also clear. This fact is undoubtedly represented in the data published by the Business Registry -statistical information regarding establishments.

In this case, when considering choosing between a PC and an LLC, the dilemma at hand is no equivalent to the one presented in the preamble (“…don’t know if I want to choose Kiki or Koko”).

Not anymore.

LLCs already seem obsolete.

P.S. A brief version of this article has been published in MAKEDONIA Newspaper (October 27th, 2019).