The remuneration of the members of the Board of Directors of an SA is a “hot” issue for everyone interested: the company, the shareholders and, of course, the beneficiary. But it also interests third parties: investors and banks. Our national legislator re-approached this issue with the law on SAs (Law 4548/2018). The procedure and conditions for granting remuneration to the members of the Board of Directors on the basis of their organic relationship were covered in our previous article (: Societe Anonyme: Remuneration of the Members of the BoD). At the present article, we will be concerned with the Remuneration Policy. A Mandatory Policy for companies with shares listed on regulated markets (Article 110 §1). A policy welcome, without a doubt, by the rest.

Remuneration of board members and conflict of interest ˙ the (global) debate

The remuneration received by the members of the Board of Directors may, under certain conditions, be detrimental to the SA. This is, moreover, a typical case of conflict of interests. It can be proven harmful when, for example, in some cases they are associated with the achievement of high goals (indicatively: the company’s turnover). It is then possible for the members of the Board of Directors to sacrifice the management of the SA by excessive risk-taking, on the altar of achievement of their, short-term, own benefit.

The recent long-term financial crisis “brought” to our country the global debate over the exorbitant fees of the members of the Board. The basis of the relevant concerns is often the lack of sufficient transparency but also the substantial participation of the shareholders in their approval. Their goal is to defend, ultimately, the corporate interest.

The achievement of this objective is pursued through the “say on pay” principle (inter: Articles 9a and 9b of Directive 2007/36/EC, as amended by Directive 2017/828/EU). Based on this principle, the remuneration of the members of the Board of Directors should be defined in such a way that the shareholders are able to express an opinion. The tool of its implementation is the Remuneration Policy (as is the Remuneration Report) which have already been transposed into national law.

Legislative framework

The national legislator regulated the matters related to the Remuneration Policy (and the Remuneration Report) in the provisions of articles 110-112 of law 4548/2018. In this way, it incorporated into Greek law the provisions of articles 9a and 9b of the aforementioned Directive-as in force.

With the Remuneration Policy (article 110 and 111 of law 4548/2018), which will concern us in this article, the strategy of the SA regarding the granting of remuneration to the members of the Board of Directors is structured. The SA’s sustainability and long-term interests are also promoted. The content of the Remuneration Report (article 112 of law 4548/2018) regards the remuneration granted to the members of the Board of Directors (or that are still due) for the previous year. It is not permissible, of course, for the paid salaries to deviate from what the Remuneration Policy stipulates.

Remuneration policy

The obligation to establish it

As we “hurried” to note in the introduction, not all SAs are obliged to adopt a Remuneration Policy. This obligation is typically borne only by companies with shares listed on a regulated market. Both for the members of the Board of Directors and for the general manager, if any, and their deputy (article 110 §1). However, with a relevant statutory regulation, it is possible to apply the provisions for the Policy and Remuneration Report in two more cases: (a) to the executives, as they are regulated by the International Accounting Standards (article 24 par. 9) and (b) to unlisted SAs. We aim, in these cases, for greater transparency towards the shareholders. For the benefit, in the end, of SA.

The obligation to establish a Remuneration Policy covers the remuneration granted to the members of the Board of Directors in their organic capacity and position. It does not cover, in other words, other fees. Such as, for example, those that are due for a special relationship of employment, mandate, independent services or works [int .: Societe Anonyme: Contracts with Members of the BoD for the Provision of (Additional) Services].

The responsibility of the General Assembly

Competent body for the approval of the Remuneration Policy is defined by law (article 110 §2) to be the General Assembly. This is a transformation of the principle we have already mentioned: “say on pay” [principle, which, however, already existed in the pre-existing national law (art. 24 par. 2 law 2190/1920)]. The shareholders’ vote is binding. In other words: the SA has no right to deviate from the decision of its shareholders.

A simple quorum and majority is sufficient for the decision of the General Assembly (for the approval, ie, or not of the Remuneration Policy). In the initial wording of Law 4548/2018, it was provided that in the relevant voting the shareholders who happened to be, themselves, members of the Board of Directors did not have the right to vote. This prohibition is no longer in place (: abolished by law 4587/2018).

In case of approval of the Remuneration Policy by the General Assembly, its duration extends, at a maximum, to four years from the relevant decision. It will, however, require further submission and approval by the General Assembly, when the conditions under which it was approved change substantially (even within four years) (Article 110 §2).

When the General Assembly is called upon to approve a new Remuneration Policy after the expiration of the previous one, it is, of course, entitled to reject it. In this case the company is bound by the Policy previously approved. The duration of the latter is extended until the next General Assembly, when a new, revised Remuneration Policy is submitted (article 110 §4).

The possibility of deviating from the Remuneration Policy

The obligation to re-submit for approval the Remuneration Policy should be distinguished from the possibility of derogation from it (Article 110 §6). The specific / provided for derogation is, in exceptional circumstances, permissible. As long as three, basic, conditions are met. Specifically:

(a) There is a relevant provision in the Remuneration Policy of the procedural conditions for the derogation.

(b) There is a relevant provision in the Remuneration Policy of the items in respect of which the derogation may occur.

(c) The need for the derogation serves the long-term interests of the company as a whole or ensures its viability.

The body responsible for submission of the Policy to the General Assembly

The Board of Directors is the competent body of the company for the submission of the Remuneration Policy to the General Assembly for approval. It is true that the specific competence of the Board of Directors does not explicitly arise from the wording of the law. On the contrary, it is derived, as a collective duty of the members of the Board of Directors, to ensure the preparation and publication, inter alia, of the Remuneration Report (article 96 §2 of law 4548/2018). However, we do not find a corresponding provision for the Remuneration Policy. This, however, does not mean that the members of the Board do not have the obligation to draft the Remuneration Policy and submit it to the General Assembly.

An different interpretation would not be compatible with the recent law on corporate governance (Law 4706/2020). As we mentioned in a previous article [The (new) law on Corporate Governance (and a comparative overview with the preexisting one)], the relevant law introduces, in addition to the Audit Committee, two additional committees of the Board (Article 10): The Nominations Committee and the Remuneration Committee. The latter is responsible for: “formulating proposals to the Board of Directors regarding the remuneration policy submitted for approval to the General Assembly, in accordance with paragraph 2 of article 110 of law 4548/2018” (: article 11 a’). In addition, it examines the information included in the Remuneration Report, providing an opinion to the Board of Directors (art. 11 par. C).

The content of the Remuneration Policy

The provisions of the Remuneration Policy must be recorded in a clear and comprehensible manner. Its (minimum) content is determined, in sufficient detail, in the provision of article 111 §1 law 4548/2018 (which constitutes an exact transposition of the relevant provisions of article 9a of Directive 2007/36/EC).

The minimum content, for example, should be the way in which this Remuneration Policy contributes to the business strategy, the long-term interests and the viability of the company. In addition, the different components for the granting of fixed and variable remuneration of all kinds as well as the criteria for their granting. The methods used to assess the degree of fulfillment of the specific criteria. The conditions for the postponement of the payment of the variable remuneration and its duration. The duration and content of the employment contracts of the members of the company’s Board of Directors – any existing retirement plans. Any share disposal rights and options. The decision-making process for the approval and determination of the content of the remuneration policy and so on.

The disclosure formalities

The central goal of the Remuneration Policy of the members of the Board of Directors is to enhance transparency. The justification is the possibility of constant information of all interested persons (especially shareholders and investors). It is therefore not paradoxical that the Remuneration Policy is made public (articles 110 §5 as well as 12 & 13). At the same time, however, it must remain available on the company’s website for as long as it is valid (art. 110 par. 5).

The existence and, in particular, the proper implementation of the Remuneration Policy of the members of the Board of Directors, constitutes an important obligation of the companies that have shares listed on a regulated market. This obligation arises from the (recent) law on Société’ Anonymes. However, it also has strong foundations in the (absolutely recent) law on corporate governance.

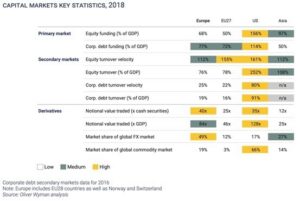

The value of the Remuneration Policy lies in the strengthening of corporate governance. And where the latter is strengthened, the companies that invest in it end up benefiting. After all, what investor will not see positively a company that has invested in corporate governance? Which bank will not, at least, increase the creditworthiness of a company with a strong relevant performance? Any relative costs for adopting a Remuneration Policy and complying with its content seem small compared to the reasonably expected benefits.

Obviously for unlisted companies as well.

Especially, perhaps, for them.-

Stavros Koumentakis

Managing Partner

P.S. A brief version of this article has been published in MAKEDONIA Newspaper (April 4, 2021).

Disclaimer: the information provided in this article is not (and is not intended to) constitute legal advice. Legal advice can only be offered by a competent attorney and after the latter takes into consideration all the relevant to your case data that you will provide them with. See here for more details.