There is a lot of discussion around the ESG criteria: for their value, the importance of their adoption by companies but also the way they are evaluated by investors, stock exchanges and the financial system. The global debate has reached our country for a long time now. The issue is no longer theoretical; it refers to attracting investment capital, to corporate creditworthiness and, ultimately, to growth. Let’s see why.

What are the ESG criteria?

ESG stands for Environmental, Social, and Governance. Specific the (: ESG) criteria are a set of standards for the operations of a company used by socially conscious investors to control potential investments. Environmental criteria examine a company’s performance as for the way they treat nature. Social criteria examine how the business manages its relationships with employees, suppliers, customers and the communities in which it operates. Governance deals with the leadership of a company, the remuneration of management and senior management, audits, internal audits and shareholder rights.

However, investors and companies are not the only ones dealing with these criteria. They are already occupying the EU. In this context, one encounters a wealth of legislation related to the ESG criteria, which highlights the high interest of the latter.

The (true) value of the ESG criteria

In 2015, world leaders unanimously approved the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. According to UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, “The Sustainable Development Goals are the path that leads us to a fairer, more peaceful and prosperous world, and to a healthier planet.”

Consequently: the issue neither has just a legislative background nor is it just of legal value.

It turns out that it has a special value for businesses as well.

George Serafeim (Professor at Harvard Business School, Chairman of the Hellenic Corporate Governance Council and Member of the Board of Directors of the Athens Stock Exchange), when introducing The ESG Information Disclosure Guide for the Athens Stock Exchange stated: companies that improve their performance in environment, social and corporate governance (ESG)… improve their access to capital, employee engagement, customer satisfaction and their relationships with society and stakeholders”.

In this Guide we read:

“sustainability has become a pertinent and pressing topic across the world, mobilizing governments… Following the call to action of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) an increasing number of companies are measuring, disclosing and managing sustainability risks and opportunities. Environmental, social and corporate governance … metrics have emerged as important factors that reflect companies’ ability to generate value and execute effective strategies…

A growing body of research has confirmed a strong relationship between performance on ESG metrics and financial performance of companies, thus demonstrating that ESSG information is financially material and therefore relevant to investors. In the absence of ESG disclosure, investors can miss important information on a company’s operations, competitive positioning and investors can miss important information on a company’s operations, competitive positioning and long-term strategy.”

The PRI

The PRI [: PRI Initiative (Principles for Responsible Investment)] is an investment initiative developed in collaboration with the UNEP Finance Initiative and the UN Global Compact, an initiative that requires participants to meet the ESG criteria.

The published data on the growing acceptance of the PRI Agreement looks impressive: This initiative already involves 170 investors managing 36 trillion (!) USD as well as 26 (!) Credit Rating Agencies (CRAs). Also: Four reports have been published as part of this initiative and more than twenty forums have been organized worldwide for industry professionals.

The principles on which the specific investors and Organizations are committed are worth mentioning:

Principle 1: We will incorporate ESG issues into investment analysis and decision-making processes.

Principle 2: We will be active owners and incorporate ESG issues into our ownership policies and practices.

Principle 3: We will seek appropriate disclosure on ESG issues by the entities in which we invest.

Principle 4: We will promote acceptance and implementation of the Principles within the investment industry.

Principle 5: We will work together to enhance our effectiveness in implementing the Principles.

Principle 6: We will each report on our activities and progress towards implementing the Principles.

ESG: Winning in the long run

From the above, there is no doubt neither about the importance that investors attach to the adoption of the ESG criteria nor about the fact that companies should (also) focus on them.

In the above context was the (relatively) recent event of the Athens Stock Exchange: ESG: Winning in the long run. The high participation in this event demonstrates the respectively high interest. There were also many interesting participations and presentations, which demonstrated the value of the adoption of the specific criteria by the companies.

We will focus on only two points of those made:

“Socially responsible companies are obviously becoming more attractive internationally and vice versa” (: Mr. Vas. Lazarakou, Chairman of the Hellenic Capital Market Commission)

“According to estimates, in the next three or four years more than 50% of the mutual funds will be invested in strategies that will have ESG criteria. (The adoption of the ESG criteria) is not something, as we would say, nice to have but it is a must have “(: Mr. Theof. Mylonas, President of the Association of Institutional Investors)

Base (also) on the specific data, the CEO of the Athens Stock Exchange, Mr. Socrates Lazaridis, announced the planning of the creation, by October, of an index that will include the sufficiently sensitized, ESG-conscious listed companies. As a natural consequence, the increase of investors’ interest in the shares of these (privileged) companies is expected.

Companies that meet the ESG criteria and investment funds

One would expect that the adoption of these criteria is only a burden (and a costly one, without any benefits) for businesses. But is that so?

Morningstar is a world-renowned financial research and investment management services company. Highly prestigious, respectively, is its research. In a relatively recent (: 30.6.20) research (: “How Does European Sustainable Funds’ Performance Measure Up?“) We find extremely interesting facts. We also find a very interesting comparative overview of the returns of Sustainable Funds in relation to the Traditional Funds.

Let us clarify at this point that Sustainable Funds are those that use environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) criteria to evaluate their investment or social impact. In contrast, traditional ones (: Traditional Funds) do not focus on the existence (or not) of such criteria for evaluating either their investments and / or their potential investments.

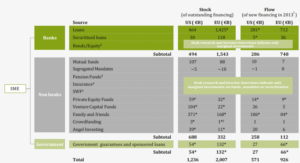

Yields and survival rate of Sustainable Funds in relation to Traditional Funds

The aforementioned Morningstar survey provides a comparative overview of Sustainable and Traditional Funds in terms of their survival rate and, above all, their returns. The superiority of the former seems obvious on a global and European level in the course of a year, three years, five years and a decade. To clarify, in the present article we focus on those parts of the research that refer to investments at global and European level, but those parts do not demonstrate significant differences from the rest of the survey.

Yields of Sustainable Funds worldwide

Below we list the performance and returns of Sustainable Funds that invest, worldwide, in large-cap companies-Blend Equity, specifically:

From the above data it appears that, in addition to the increased survival rate of Sustainable Funds, their average returns from the aforementioned investments range from 6.9% over a decade to 25.7% year-on-year. In contrast, the average returns of Traditional Funds are limited to 6.3% over a decade and reach 23.3% year-on-year.

Yields of Sustainable Funds investing in Europe

Below we list the performance and returns of Sustainable Funds investing in Europe-also in large-cap companies -Blend Equity˙ specifically:

The survival rates of Sustainable Funds are, in this case, extremely high compared to Traditional Funds. The returns of Sustainable Funds, which invest in these European companies, are also increased: they range from 6.8% over a decade to 26.2% year-on-year. In contrast, the average returns of Traditional Funds are limited to 6.6% over a decade and reach up to 24.2% year-on-year.

Yields of Sustainable Funds investing in the Eurozone

Below we list the performance and returns of Sustainable Funds investing in the Eurozone in large cap companies -Blend Equity, specifically:

The survival rates of Sustainable Funds are, in this case as well, extremely high compared to Traditional Funds. Respectively, the average returns of the Sustainable Funds that invest in the Eurozone in the specific companies range from 5.6% in a decade to 24.4% year-on-year. On the contrary, the average returns of Traditional Funds are limited to 5.5% over a decade and reach up to 23.7% year-on-year.

Conclusion

From the above, the conclusion is that those Funds (: Sustainable Funds) that focus on investments with ESG criteria have obviously better survival rates but also better returns than the others (: Traditional Funds). Companies, therefore, that meet these (: ESG) criteria are the ones that will receive the “lion’s share”, in terms of the interest of significant investors. The necessary funds for their growth and their development in the end seem to be, this way, easier to come across and it is safer to bet on receiving them.

The interest of the global community, investment funds and stock exchanges (and most recently financial institutions), emerges as a clear manifestation of the adoption of the ESG criteria. Consequently, their adoption by large-cap companies, but also by those whose shares are listed on regulated markets, seems to be extremely important.

The issue, however, should not concern the specific larger companies only. (It should) concern all businesses that are (or are likely to be) targeted by investors. Those whose creditworthiness is assessed. Those who either want to showcase their achievements in these areas or are simply evaluated by them.

It is important to remember, however, that the younger generations of consumers are not only interested in the value for money of the product or service they buy.

It is, therefore, obvious that the adoption of the ESG criteria by some companies, puts them in an (on many levels) advantageous position. (In this context we also find the “Equality Mark” awarded to companies provided by the bill for labor issues – see our article to follow).

The relevant ESG “passport” is therefore necessary for the development and, in some cases, the survival of businesses.-

Stavros Koumentakis

Managing Partner

P.S. A brief version of this article has been published in MAKEDONIA Newspaper (June 6, 2021).

Disclaimer: the information provided in this article is not (and is not intended to) constitute legal advice. Legal advice can only be offered by a competent attorney and after the latter takes into consideration all the relevant to your case data that you will provide them with. See here for more details.